Bastille Day Tragedy: Nice Lorry Attack: Difference between revisions

Roxana (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Dinu (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|Use Cases Category=Real-world | |Use Cases Category=Real-world | ||

|Year=2016 | |Year=2016 | ||

|Publishing Organisation=Deutsche Hochschule der Polizei (DHPol) | |||

|Location=Nice, France | |Location=Nice, France | ||

|Event type=Terror | |Event type=Terror | ||

| Line 14: | Line 15: | ||

The French government declared three days of national mourning starting on 16 July and since the attack was declared an act of terrorism, the French President François Hollande announced an extension of the state of emergency for additional three months (which had been declared following the attacks in Paris in November 2015), later, France extended the state of emergency until 26 January 2017. Moreover, government officials called for "patriotic citizens" to join the reserve forces to boost the French security and add around 12,000 police reservists to the 120,000-person force . | The French government declared three days of national mourning starting on 16 July and since the attack was declared an act of terrorism, the French President François Hollande announced an extension of the state of emergency for additional three months (which had been declared following the attacks in Paris in November 2015), later, France extended the state of emergency until 26 January 2017. Moreover, government officials called for "patriotic citizens" to join the reserve forces to boost the French security and add around 12,000 police reservists to the 120,000-person force . | ||

|Involved Organisations=Police Nice, French Government | |||

|SMCS usage problems solving=Crisis communication | |||

|Use cases thematic=Ensuring Credible Information, Making Information Accessible, Mobilising Volunteers | |Use cases thematic=Ensuring Credible Information, Making Information Accessible, Mobilising Volunteers | ||

|Limitations=The first tweet was written 13 minutes after the attack, addressing the local media (@Nice_Matin) and asking if they had any information regarding an attack. The information flow on the events on social media was relatively slow as compared to similar attacks, with relatively little first-hand information from the scene in the first fifteen minutes. Social media analyses flag the problem that firsthand information (particularly such that could have triggered alert systems) was not easily accessible because users did not necessarily use hashtags to relate to the events in a structured manner or understood what was happening or the full gravity of the events they started to share images from. | |Limitations=The first tweet was written 13 minutes after the attack, addressing the local media (@Nice_Matin) and asking if they had any information regarding an attack. The information flow on the events on social media was relatively slow as compared to similar attacks, with relatively little first-hand information from the scene in the first fifteen minutes. Social media analyses flag the problem that firsthand information (particularly such that could have triggered alert systems) was not easily accessible because users did not necessarily use hashtags to relate to the events in a structured manner or understood what was happening or the full gravity of the events they started to share images from. | ||

Many official Tweeter accounts from local first-responder organization, as well as the regional crisis center, did not tweet at all that night. The local police (@PMdeNice) was the first official account to post about the events on social media: at 23:49 they sent a message in French via Twitter, asking citizens to stay inside their homes because of ongoing police operations. Yet, it was not until after 00:37 that official accounts began to mention the term “attack” in relation with the location. This was done purposefully to counter rumors about a hostage situation which had started to spread. However, the local press (@NiceMatin) had disclosed the attack and location already at 23:00, and the TV (@BFMTV) had tweeted breaking news about it at 23:43. This led to citizens interacting much more with the press than with first responders in charge of the crisis management. According to research, interactions with first responders increased a bit throughout the night but official accounts failed to publish enough tweets to cope with the publics need for information – providing little feedback or expressions of support. | Many official Tweeter accounts from local first-responder organization, as well as the regional crisis center, did not tweet at all that night. The local police (@PMdeNice) was the first official account to post about the events on social media: at 23:49 they sent a message in French via Twitter, asking citizens to stay inside their homes because of ongoing police operations. Yet, it was not until after 00:37 that official accounts began to mention the term “attack” in relation with the location. This was done purposefully to counter rumors about a hostage situation which had started to spread. However, the local press (@NiceMatin) had disclosed the attack and location already at 23:00, and the TV (@BFMTV) had tweeted breaking news about it at 23:43. This led to citizens interacting much more with the press than with first responders in charge of the crisis management. According to research, interactions with first responders increased a bit throughout the night but official accounts failed to publish enough tweets to cope with the publics need for information – providing little feedback or expressions of support. | ||

Similar to the attacks in Paris, Brussels, Stockholm, Barcelona, and Munich, citizens immediately, while it still remained unclear whether the threat had ended, people used social media, particularly Twitter, to help each other. Using the hashtag #PortesOuvertesNice (Open | Yet, after the first hour, a great deal of the discourse on social media shifted to political controversies or to expressions of outrage concerning news coverage which drowned information relevant for the emergency management again. Later, a lot of false information was added to the already dysfunctional dynamics – e.g., that hostages had been taken, that the Eiffel Tower had been set on fire, and that Cannes had also been attacked. On 14 and 15 July, the French government even urged social media users to only share information from official, reliable sources. | ||

|Worked well=Similar to the attacks in Paris, Brussels, Stockholm, Barcelona, and Munich, citizens immediately, while it still remained unclear whether the threat had ended, people used social media, particularly Twitter, to help each other. Using the hashtag #PortesOuvertesNice (Open Doors Nice), they established a crowd-enabled support network to offer shelter or food for those in need. | |||

|Additional links=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36800730, https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/nizza-anschlag-101.html, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_Nice_truck_attack, | |||

'''Crisis Communication:''', | |||

[https://links.communitycenter.eu/index.php/ATTACKS_in_public_places Attacks in public places] | |||

|Other images=terror_nice_1.jpeg, terror_nice_2.jpeg, terror_nice_3.jpeg, terror_nice_4.jpeg | |||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:41, 29 November 2023

Last edited: 29 November 2023

Hazard:

TerrorYear:

2016Location:

Nice, FranceScale:

CityInvolved Organisations:

Police Nice, French GovernmentPublishing Organisation

Deutsche Hochschule der Polizei (DHPol)

Category

Real-world

Theme

Social Media

Thematic

- Ensuring Credible Information

- Making Information Accessible

- Mobilising Volunteers

Disaster Management Phase

After, During

Description

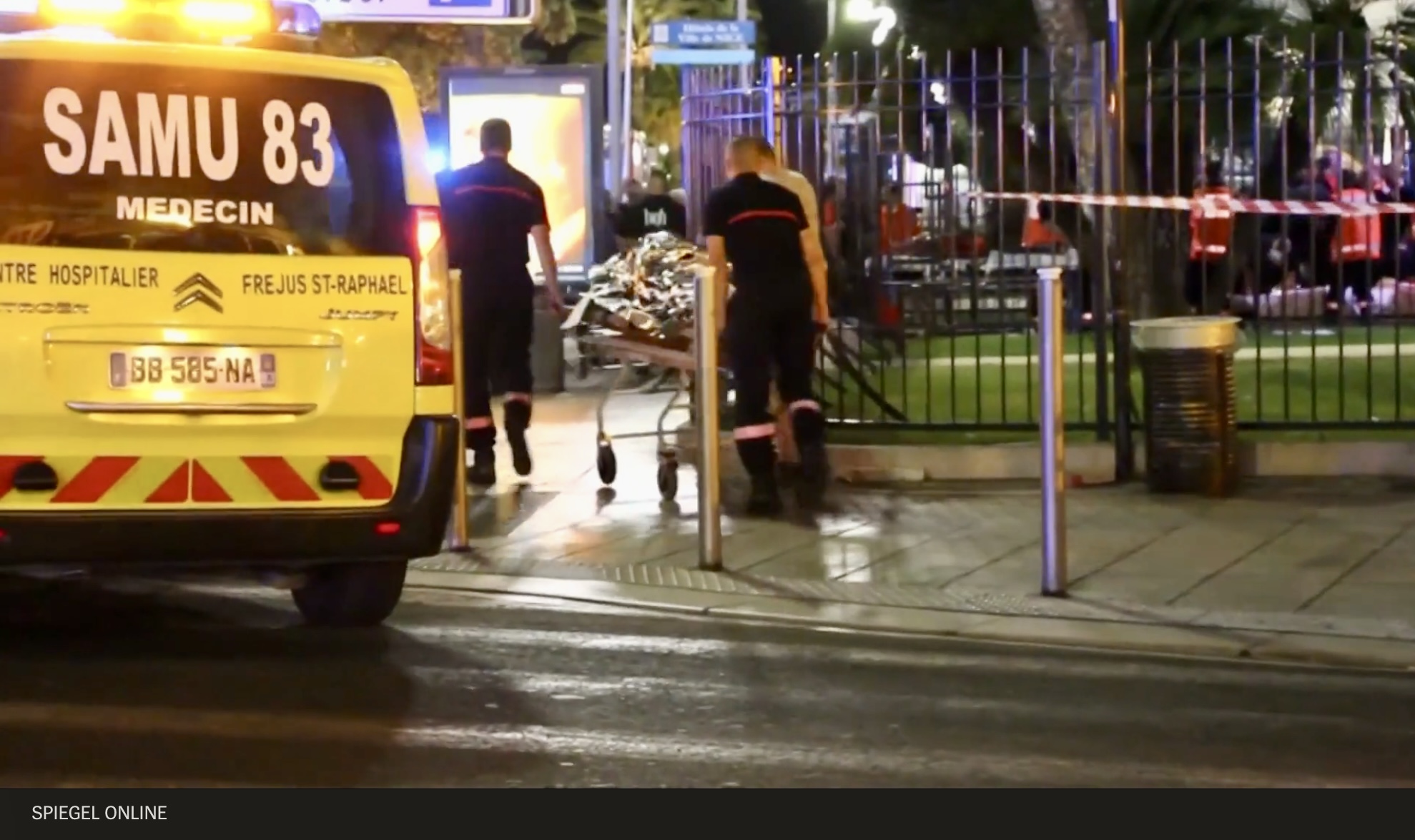

The entire attack took place over a distance of 1.7 kilometers and lasted about five minutes. Zigzagging along the seafront, the perpetrator was able to kill 86 people and injured more than 200 before he was finally killed in a shootout with two national police officers. On 15 July, François Molins, the prosecutor for the Public Ministry, officially stated that the attack bore the hallmarks of jihadist terrorism. Later investigations revealed that the attacker, a 31-year-old man of Tunisian nationality with a French residency permit, was known to French authorities only for threatening behavior and petty crimes and became radicalized only shortly before the attack. Yet, he is believed to have planned the attack for several months and to have had help from accomplices. Six suspects were later charged with "criminal terrorist conspiracy", three of whom also charged for complicity in murder, three further suspects were charged for supplying the perpetrator with illegal weapons.

The French government declared three days of national mourning starting on 16 July and since the attack was declared an act of terrorism, the French President François Hollande announced an extension of the state of emergency for additional three months (which had been declared following the attacks in Paris in November 2015), later, France extended the state of emergency until 26 January 2017. Moreover, government officials called for "patriotic citizens" to join the reserve forces to boost the French security and add around 12,000 police reservists to the 120,000-person force .What was the overall goal of the Use Case?

Crisis communicationWhat worked well and could be recommended to others?

Similar to the attacks in Paris, Brussels, Stockholm, Barcelona, and Munich, citizens immediately, while it still remained unclear whether the threat had ended, people used social media, particularly Twitter, to help each other. Using the hashtag #PortesOuvertesNice (Open Doors Nice), they established a crowd-enabled support network to offer shelter or food for those in need.What limitations were identified?

The first tweet was written 13 minutes after the attack, addressing the local media (@Nice_Matin) and asking if they had any information regarding an attack. The information flow on the events on social media was relatively slow as compared to similar attacks, with relatively little first-hand information from the scene in the first fifteen minutes. Social media analyses flag the problem that firsthand information (particularly such that could have triggered alert systems) was not easily accessible because users did not necessarily use hashtags to relate to the events in a structured manner or understood what was happening or the full gravity of the events they started to share images from.

Many official Tweeter accounts from local first-responder organization, as well as the regional crisis center, did not tweet at all that night. The local police (@PMdeNice) was the first official account to post about the events on social media: at 23:49 they sent a message in French via Twitter, asking citizens to stay inside their homes because of ongoing police operations. Yet, it was not until after 00:37 that official accounts began to mention the term “attack” in relation with the location. This was done purposefully to counter rumors about a hostage situation which had started to spread. However, the local press (@NiceMatin) had disclosed the attack and location already at 23:00, and the TV (@BFMTV) had tweeted breaking news about it at 23:43. This led to citizens interacting much more with the press than with first responders in charge of the crisis management. According to research, interactions with first responders increased a bit throughout the night but official accounts failed to publish enough tweets to cope with the publics need for information – providing little feedback or expressions of support.

Yet, after the first hour, a great deal of the discourse on social media shifted to political controversies or to expressions of outrage concerning news coverage which drowned information relevant for the emergency management again. Later, a lot of false information was added to the already dysfunctional dynamics – e.g., that hostages had been taken, that the Eiffel Tower had been set on fire, and that Cannes had also been attacked. On 14 and 15 July, the French government even urged social media users to only share information from official, reliable sources.